Hurricane Earl

Status: Closed

| Type of posting | Posting date(EST): | Summary | Downloads |

|---|---|---|---|

| Landfall | 8/4/2016 2:00:00 PM |

|

Landfall | Summary

Posting Date: August 4, 2016, 2:00:00 PM

With heavy rain and the threat of storm surge, flash flooding, and mudslides, Category 1 Hurricane Earl made landfall southwest of Belize City, Belize, just after midnight local time on August 4. Earl downed power lines, toppled trees, and caused coastal flooding as it moved through the Caribbean en route to the Yucatan Peninsula, prompting hurricane and tropical storm warnings throughout the region. At least six people are reported to have been killed. The storm steadily weakened as it moved across Belize, Guatemala, and into southern Mexico, yet it is expected to continue to deliver heavy rainfall.

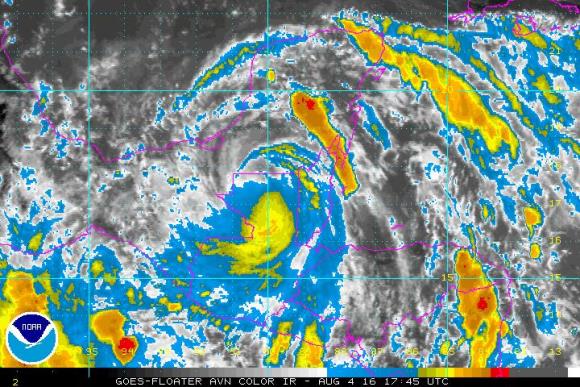

Hurricane Earl on August 4, 2016, at 16:17 UTC. (Source: NOAA)

Meteorological Summary and Forecast

Earl became the fifth named storm of the Atlantic hurricane season Tuesday morning, August 2, when the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Hurricane Hunter reconnaissance confirmed the formation of an area of low pressure. A day later, with Earl near the coast of Honduras, the storm gained hurricane status when NOAA reported winds of 120 km/h (75 mph).

As a Category 1 hurricane, Earl made landfall southwest of Belize City, Belize, August 4 at 12:04 a.m. CST (06:04 UTC), with a minimum pressure of 979 mb and maximum sustained winds of 130 km/h (81 mph). The first hurricane to make landfall in the western Caribbean Sea west of Jamaica since Hurricane Ernesto on August 7, 2012, Earl arrived with a flooding storm surge and heavy rain. Wind gusts as high as 93 km/h (58 mph) were reported west of Belize City, at Philip Goldston International Airport. Hurricane-force winds reportedly extended only 24 km (15 miles) from the eye, although tropical storm–force winds reached significantly farther, 225 km (140 miles).

For the next 36 to 48 hours, a high-pressure ridge situated north of the storm is expected to keep Earl moving westward to west-northwestward. Rain—not wind—remains the dominant hazard, with precipitation totals as high as 450 mm (18 inches) possible in parts of Guatemala and southern Mexico. In Mexico, the Yucatan Peninsula and the states of Tabasco and Veracruz are particularly at risk.

Some chance exists for the storm to cross the southern Bay of Campeche—site of numerous Petroleos Mexicanos (Pemex) oil rigs and platforms—but Earl has now weakened to a tropical depression and is not likely to spend enough time over the bay to reintensify. Although Earl is projected to travel far south of the U.S. coast, storm-related showers are expected to impact South Texas this weekend, and high surf and rip currents could affect the Texas coast, possibly up to Galveston.

After four days, Earl (or what remains of Earl) is projected to pass over the mountains of central Mexico, leading to the storm’s dissipation.

Hurricane Earl track, as of 10:00 a.m. CDT (16:00 UTC) on August 4, 2016. (Source: NHC)

Reported Impacts and Damage

Hurricane warnings were issued for the Belize coast, including Belize City, and along the Mexico coast to Puerto Costa, including Chetumal. Tropical storm warnings were issued for the Mexico coast to Punta Allen, but did not include the popular tourist destinations of Cancun or Cozumel.

In coastal areas, storm surge could result in localized flooding. In addition, waves accompanying the surge could exacerbate flooding and beach erosion. Inland, drenching rain in Belize, Guatemala, and southern Mexico could result in life-threatening flash floods and mudslides.

In Belize, storm shelters were opened prior to landfall, and residents of low-lying ground were encouraged to evacuate. In addition, government officials closed Philip Goldston International Airport, as well as archaeological reserves and national parks, and the Tourism Board canceled cruise ship calls for the week. Belize City experienced flooding from storm surge of up to 2 meters (6 feet). Also, the National Meteorological Service of Belize reported power outages throughout the country.

Along coastal Guatemala, some low-lying areas were evacuated prior to the storm’s arrival.

In the Mexican state of Quintana Roo, along the coast north of the projected track, shelters were prepared and some evacuations reported.

Prior to becoming a named storm, the tropical disturbance that would become Earl resulted in six deaths in the Dominican Republic Sunday when power lines fell on a bus, causing a fire. On Tuesday, Earl brought heavy rain to Jamaica and the Cayman Islands. On Wednesday, Earl’s rain drenched Honduras, while the storm’s high winds knocked down utility poles and damaged trees, resulting in school closures and flight cancellations.

Exposure at Risk

The most concentrated exposures in Central America and Mexico are in urban centers, which consist mainly of capital cities and resort towns. Urban centers have a high density and diversity in building types, from residential single-story houses to high-rise apartments to hotels to religious and cultural centers. However, the rate of rapid growth within Central American and Mexican cities is exacerbating already highly concentrated areas in a way that is increasing hazard risk. Poor, rural families are migrating to cities at high rates and building poorly designed structures along city outskirts. These structures can be feebly made and situated in precarious locations, such as on hillsides. Development of urban slopes increases the risk of flooding in the surrounding low-lying areas, which often corresponds to the urban centers.

In Belize, Guatemala, and Mexico, inland exposure concentrations are at risk from precipitation-induced flooding. Heavy rainfall can produce flooding in two ways: rain flows down slopes and collects in low-lying areas, and rainfall causes river- and streambeds to overflow and flood surrounding regions. Flash flooding from sustained rainfall can result in damage to unprotected building contents, as well as structures.

The predominant construction types for insured residential buildings in these countries are masonry and concrete. Masonry buildings can better resist the wind uplift load than wood frame buildings, due to their mass. For apartments, reinforced masonry or concrete is used predominantly. High-rise apartment buildings, in contrast, are chiefly constructed of reinforced masonry, reinforced concrete, or steel, and wind damage to these buildings is typically restricted to nonstructural components, such as windows, wall sidings, and roofs. Commercial building stock is heterogeneous, varying from poorly constructed low-rise masonry structures to well-maintained steel buildings, although concrete and masonry are the main construction types; wind damage to commercial buildings is usually restricted to nonstructural components, such as windows and wall sidings.